Broken Doctors, Broken Systems: Clinician Mental Health in Context.

Modified from a Plenary Talk at Combined Annual Scientific Congress of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists. May 2018. @DrEricLevi

How do you deliver the best care for your patient? More importantly, how do you deliver the best care for your patient in the context of institutional and individual challenges? The problem of clinician burnout and mental health is well known. As individuals and institutions, we have been grappling with this issue for some time. We have had many interventions with variable successes. Are we thinking correctly around this?

I would like to change your mind on this matter. I have no disclosures. I do have a disclaimer. I am not a psychiatrist or a mental health professional. I am a surgeon on the coalface. I have been hit by friendly fire and covered in mud. I would sincerely like to share my thoughts as a front-line worker and offer three possible practical action plans that are not necessarily expensive or extensive to tackle this issue.

Doctor wellbeing and doctor suicides are uncomfortable topics for many of us. We are trained to diagnose, treat, gas, tube, stabilise, fix patients. Unlike our colleagues who are GPs and Psychiatrists, we are uncomfortable with this “wishy-washy, touchy-feely” stuff. We know it is important somehow but we don’t know how to approach it. We are not trained to help our colleagues. We don’t know how to respond to a struggling colleague. There is a certain awkwardness when we see our colleagues struggle.

We know that there is an elephant in the room but we don’t really know what to do with that elephant. The data is clear and has been covered in many other places. Doctors are struggling, and they are struggling quietly. (National Mental Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students. October 2013. Beyond Blue.) These are the numbers we know in Australian Doctors in 2013 based on Beyond Blue survey of over 12,000 doctors: 1 in 5 has been diagnosed with or received treatment for depression. 1 in 4 has had suicidal thoughts. And 1 in 50 has attempted suicide. The risk with us looking at these statistics is our cognitive dissociation from this statistic the same way we look at other statistics and say “those numbers are for the patients, not for me.” No, this is our statistic. This is us in this room. This is the state of our health care community. In a typical Surgical or Anaesthetic Department, there will be someone who has had thoughts of suicide and perhaps someone who has attempted suicide. Females are at higher risk, and the specialty hotspots for suicide are GP, ED and anaesthesia. However, it’s not a gender issue because males commit suicide. It’s not an age issue, because consultants commit suicides, not just trainees. I am mindful that there may be some of us struggling with these thoughts this week, or even right now. If that is you, please hear me. You really matter. You really do matter to your community, to us, and to our patients. Please share your burden with a trusted colleague, a GP or a professional mental health worker. Help us help you to be a better doctor for your patient.

In view of this elephant in the room, self-care and managing mental health is indispensable. It’s so important that for the first time last year, the World Medical Association has included self-care as part of their Physician’s Pledge on the Declaration of Geneva. The Physician’s Pledge is the modern version of the Hippocratic Oath. In 2017 it begins with: “AS A MEMBER OF THE MEDICAL PROFESSION, I SOLEMNLY PLEDGE to dedicate my life to the service of humanity”. And then further down the pledge it says: “I WILL ATTEND TO my own health, well-being, and abilities in order to provide care of the highest standard”.

I cannot stress enough the importance of mental health and self-care in our caring profession. This is why resilience training, personal coaching, having a GP or a professional mental health worker are important and have been shown to improve the way we deal with workplace stresses. If you suffer from mental illness, getting good treatment is critical to your delivering care of the highest standards for our patients.

The big question I would like to pose is this: Is that enough? Is resilience training, mindfulness & coaching the solution to our problems? For that particular elephant, yes.

May I change your mind? I’d like to suggest that there may be another elephant in the room? If we call the first elephant mental health, can I call the second one Institutional Health?

I am sure you know what I mean by institutional Health: Workplace conditions, relational toxicity, administrative intrusions, time pressures, excessive workload, resource limitations, competition for jobs, poor job satisfaction, poor job engagement, bullying, harassment, sexism, job maldistribution, etc.

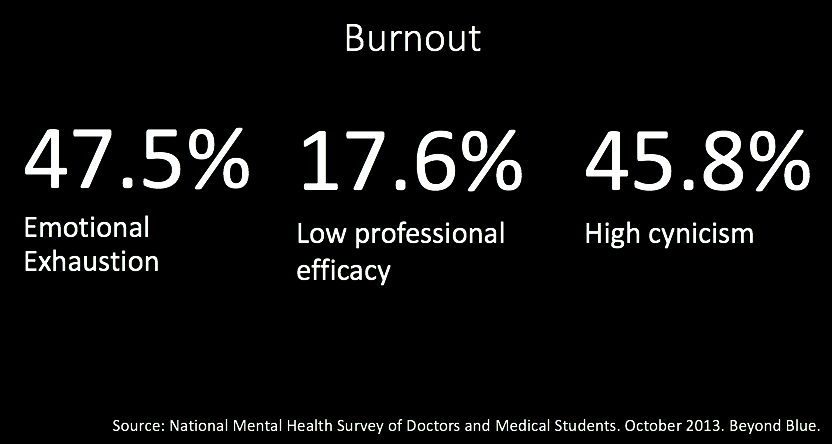

Burnout. This is Australian data again from the same Beyond Blue Survey. Burnout is defined as a psychological state characterised by emotional exhaustion, low job efficacy and high cynicism or depersonalisation, due to chronic occupational stress in the caring profession. It is not a DSM5 or ICD10 mental illness diagnosis. It is a psychological state due to workplace stress. Workplace factors have strong association with burnout. Half of us are emotionally exhausted, 1 in 6-7 not effective, and half of us are highly cynical. Burned-out doctors are bad for patients, and bad for business. They’re ineffective. They may order more unnecessary tests, take longer to complete tasks, make mistakes, and do not deliver high standards of care. How can you care for a patient when you are emotionally exhausted and cynical?

Burnout. This is Australian data again from the same Beyond Blue Survey. Burnout is defined as a psychological state characterised by emotional exhaustion, low job efficacy and high cynicism or depersonalisation, due to chronic occupational stress in the caring profession. It is not a DSM5 or ICD10 mental illness diagnosis. It is a psychological state due to workplace stress. Workplace factors have strong association with burnout. Half of us are emotionally exhausted, 1 in 6-7 not effective, and half of us are highly cynical. Burned-out doctors are bad for patients, and bad for business. They’re ineffective. They may order more unnecessary tests, take longer to complete tasks, make mistakes, and do not deliver high standards of care. How can you care for a patient when you are emotionally exhausted and cynical?

What is the relationship between mental illness diagnosis of depression and workplace illness of burnout? We are still exploring that. Some say causative, others say associative, still others say they are overlapping conditions, and some say they’re essentially the same thing. Perhaps they’re different conditions due to their aetiology or cause, but may result in a similar constellation of symptoms. For example, you can have depression and not be burned out by work. On the other hand, you can be absolutely burned out at work and not have the DSM5 diagnosis of major depression. This is why some people find that a change of work environment results in a significant change of emotional state and engagement at work. This is why a doctor with depression that is well managed can be an effective engaged worker that delivers high standards of care. This is exactly why we need to tackle the issue of mandatory reporting in some Australian states. A doctor with mental illness does not equal an unsafe doctor. A doctor with mental illness may provide a safe and efficient care just the same as a doctor with cardiac or respiratory illness.

There is an elephant in the room we’ve called mental health. But there is another elephant sitting on the chest of our clinicians that I would call institutional health. How did we come to this? How did we get the best and brightest, the A-students in high school and university, the ones who worked hard through school, medical school, specialist training, how did we end up then with doctors who are burned out and ready to quit medicine or quit life altogether?

Some of you might think “Oh, just toughen up princess. I used to do longer hours than you.” Perhaps that is true, but it’s not the duration but the quality of the work that has changed over time. Limiting work hours have made no difference to rates of burn out. Our patients are getting more complex, new diagnoses and treatments are being discovered everyday, the administrators and lawyers are intruding our work space. In the past, daily work may have included a higher proportion of clinical work. Today, much of our work is non-clinical. It’s data entry, paperwork, organisational, research, etc. We actually spend very little time with patients. Medicine is no longer what it used to be. You have to log in 27* times before you see a patient and choose one of 273* algorithms or protocols for your patient (*not real data). The link between workplace stressors and clinician burnout is confirmed through several studies already.

Last year I burned out spectacularly. I was snappy and I was a horrible person to be with and work with. So like a good Generation X doctor, I wrote a blog. I titled it the Dark Side of Doctoring. The blog was triggered by a suicide death of a Brisbane gastroenterologist but it hit me hard because I was in a dark place. I wrote mostly to pen down my emotions, but somehow it went viral and was read 288,000 times. That is, more than a quarter of a million people have read that blog. A lot of clinicians simply identified with the feelings I had. The content was simple. I spoke about the 3 things I lost during my surgical training and my life as a surgeon

Firstly: Loss of control. Everyday my life is dictated by clinics, operating theatre and emergencies. We are slaves to our pagers and on call roster. Every year I get moved to different hospitals. Every day I am pressured to do more. I am told where to be, what to do and who to operate on.

Secondly: Loss of support. I was studying and didn’t see my family. I miss out on birthdays, anniversaries, family holidays. I didn’t have anyone to talk to because everyone was busy. No one understood the pressures of the work I do

And finally, but most importantly, I had a loss of meaning. I lost the purpose of my work because it all became a burden. What really matters, patient care, is lost in the noise and buzy-ness of work.

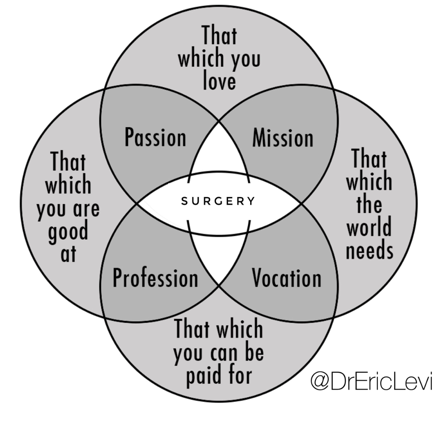

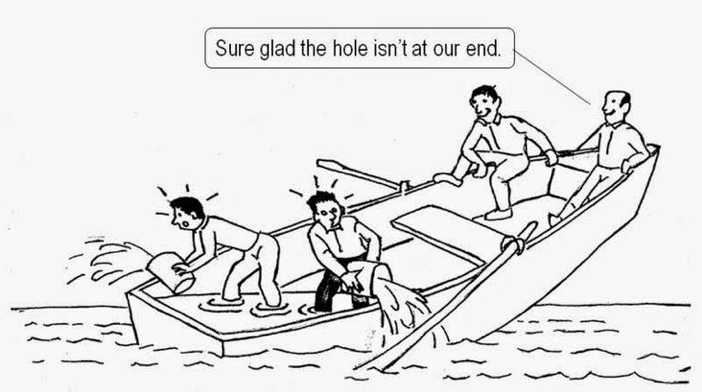

I started surgery with this idea in mind, that surgery was my Ikigai, a Japanese concept. What I love, what the world needs, what I can get paid for and what I’m good at, all overlapping and I find meaning through surgery at the centre. I lost all that. The truth is many of us in this room would know that such is the noble calling and purpose of our work. But we lost it. We lost what mattered. But it wasn’t a sudden thing. It was always small little things during the day over many years that slowly push us closer and closer to the edge. The loss of control, the loss of support, the loss of meaning, the exams, the research deadlines, the gender inequity, the toxic workplace, the bullying, the resource limitations, every small thing brings us closer to the edge of quitting. Daily, chronic, repetitive emotional microtrauma. It’s like the analogy of the frog in the boiling water. Every microtrauma we experience every day is another degree up on the water temperature. We can’t keep training the frog resilience. It is not enough. We need to fix the boiling environment. Resilience is a personal solution. We must design institutional solutions to institutional problems. That’s why holidays aren’t enough. We can’t just leave the room for a bit and hope the elephants will go away. You’ll be back in the room and still face the same elephants.

I started surgery with this idea in mind, that surgery was my Ikigai, a Japanese concept. What I love, what the world needs, what I can get paid for and what I’m good at, all overlapping and I find meaning through surgery at the centre. I lost all that. The truth is many of us in this room would know that such is the noble calling and purpose of our work. But we lost it. We lost what mattered. But it wasn’t a sudden thing. It was always small little things during the day over many years that slowly push us closer and closer to the edge. The loss of control, the loss of support, the loss of meaning, the exams, the research deadlines, the gender inequity, the toxic workplace, the bullying, the resource limitations, every small thing brings us closer to the edge of quitting. Daily, chronic, repetitive emotional microtrauma. It’s like the analogy of the frog in the boiling water. Every microtrauma we experience every day is another degree up on the water temperature. We can’t keep training the frog resilience. It is not enough. We need to fix the boiling environment. Resilience is a personal solution. We must design institutional solutions to institutional problems. That’s why holidays aren’t enough. We can’t just leave the room for a bit and hope the elephants will go away. You’ll be back in the room and still face the same elephants.

The good news is that we can do something about institutional health. But it will take ownership of the problems and courageous leadership towards solutions. We must go from “They change or they die” to “We change or we die.” This is our problem as healthcare community and we need to find practical solutions ourselves. Other institutions are already ahead in this journey and have given us some ideas:

The good news is that we can do something about institutional health. But it will take ownership of the problems and courageous leadership towards solutions. We must go from “They change or they die” to “We change or we die.” This is our problem as healthcare community and we need to find practical solutions ourselves. Other institutions are already ahead in this journey and have given us some ideas:

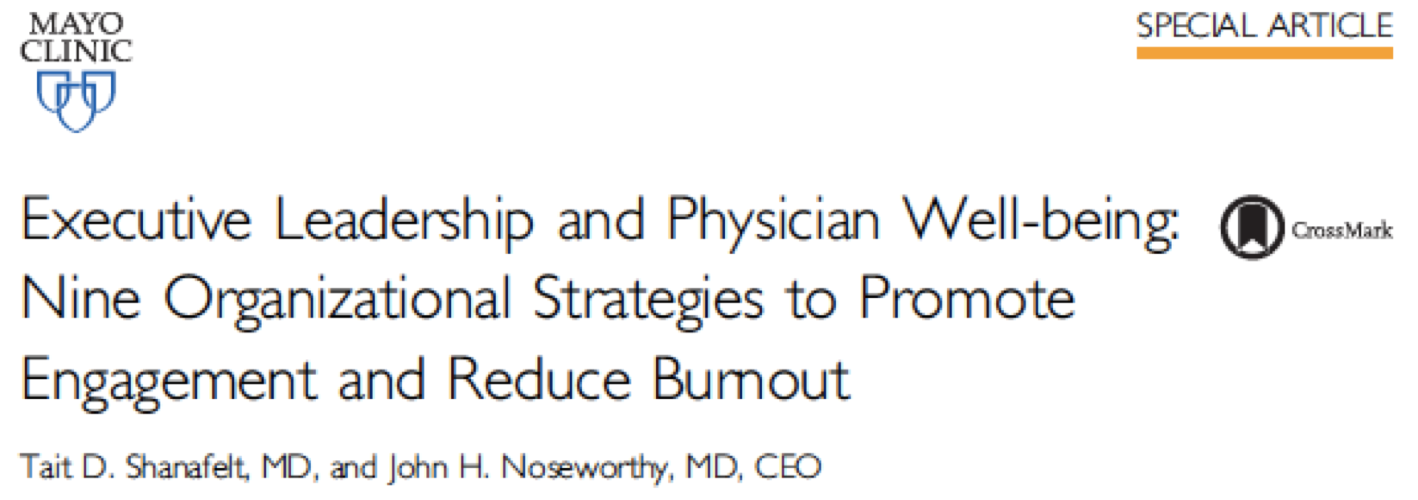

Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, and John H. Noseworthy, MD, CEO. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129-146.

This paper is a must read for all of us, whether or not we are in positions of leadership. It provides multiple practical ways of measuring institutional health and suggests 9 key strategies on tackling this issue. Resilience training is number 8. The rest are aimed at the other elephant. The solutions are absolutely practical. There are measurable goals for any department and institution. I implore you to read this paper thoroughly. Summarising it here will not do justice to the excellent paper that it is. It provides multiple practical metrics on institutional health and practical interventions on improving those metrics. Let me reiterate: it is a must read.

There is already a national framework on the matter of Doctors and Mental Health. The ANZCA has some clear plans. The RACS have made great strides in creating an Action Plan for Cultural Change and Leadership from the top. Various Hospitals and Departments around Australia and New Zealand are on active discussion around this issue. I absolutely believe that there is a momentum already occurring around this issue and that we are close to tipping point. I absolutely believe that.

So what can I do now? What practical things should I do?

Here comes the Action Points and homework. Please think carefully about these 3 Cs and how they apply to you, your department and your hospital.

- CORE. Find your core business. What is your meaningful work? One way to combat burnout is to ensure that you are doing enough of work that you find meaningful. One fascinating research done and explained in the same paper is the 20% rule. Evidence suggests that doctors who spend at least 20% of their professional effort focused on the dimension of work they find most meaningful are at dramatically lower risk for burnout (Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sloan JA, et al. Career fit and burnout among academic faculty. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10): 990-995). Although each 1% reduction below this threshold increases the risk of burnout, there is a ceiling effect to this benefit at 20% (eg, spending 50% of your time in the most meaningful area is associated with similar rates of burnout as 20%). This suggests that doctors will spend 80% of their time doing what Institutions need them to do provided that they are spending at least 20% of their time in the professional activity that motivates them. This activity could involve caring for specific types of patients (eg, the poor, refugees) or patients with a given health condition (eg, becoming a disease expert) or activities such as patient education, quality improvement work, community outreach, mentorship, teaching students/residents, or leadership/administration. To harness this principle, you must know what that 20% activity is so you can facilitate professional development in that dimension. Find your core and modify your work schedules to meet that.

- CHAMPION. Find a champion in your department. You do not have to have a leadership position to be influential in your department. It’s a myth to think that you need to be a unit Leader to make a difference. Find the welfare champions in your unit. Someone who could be the welfare officer to initiate some actions for your department. Someone who could keep an eye on measuring the institutional health of the unit. That person could be you or could be your colleague. Tap them on the shoulder and start coming up with simple creative ideas to improve the health of the team. Use that Shanafelt paper as a discussion primer as they have curated and created a list of measurable evidence based interventions. It doesn’t have to be expensive or extensive. Perhaps, you can one day even formalise the role and have a wellness officer in each unit responsible for these matters. Not a social secretary for beer. A wellness officer to improve the health of the unit.

- CULTURE. This is the big one. Cultural change will require a departmental, college and state action. One of the key things in any effective change is leadership buy-in and commitment. We are not just talking about the departmental head, but the CEO or the head of the workforce department. This will require some longer-term plans, but it is absolutely possible and doable. There is already a good momentum and I believe we are almost at tipping point. I can give multiple North American examples of how top down leadership has improved patient care and turned hospitals around but I will quote a local example. The Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne has started this journey a couple of years ago. They came up with a new Clinician Compact. Several key statements that define the values of the organisation are reiterated, like a pledge. They started at the top to include all clinical and administrative staff. This was their way of tackling an institutional elephant to change culture and to improve the care for every child. The College of Surgeons too, have defined a cultural change campaign with the “Operating with Respect” initiative. We have momentum. We can do this to deal with the institutional health elephant.

Now the elephants in your departments in Melbourne, Auckland or Christchurch are going to look different. With the current momentum that we already have, small changes will make big differences. We can begin with finding our personal Core business and meaningful work to improve our personal job satisfaction and efficacy. We can then find Champions in our departments to improve the unit welfare. We can then in the longer-term effect cultural change with collaboration. Dealing with the institutional health will go a long way in improving mental health. We need to tackle the mental health and institutional health elephants at all levels. Individual mental health treatment approaches, Departmental action plans, Hospital cultural change campaigns, Statewide initiatives, National policies and College level directives. Multifactorial approaches to the elephants.

A proverb says, “One generation plants the trees, another gets the shade.” Seed has been planted. Momentum is already built. Many clinicians have been working in this arena for many years. This generation and the next will get the shade.

We owe this to our patients. Our patients matter and they deserve mentally & physically healthy doctors and healthy institutions.

Downloadable PDF transcript here: Broken Doctors Broken Systems Transcript. Feel free to use and share it as you see fit for your colleagues and patients.