Speed trumps perfection. Safety is a priority. This coronavirus pandemic has created a tsunami of innovation and collaboration. New problems are identified and creative solutions are offered across specialty lines. Many Ear Nose and Throat Surgeons in Australia and New Zealand use a special spectacle-mounted headlight magnifying loupes to look into ears, noses & throats (Vorotek).… Read more

Category: Uncategorised

New Zealand ENT News

From my ENT colleagues and for my ENT colleagues across the Tasman as of 31st March 2020. THINGS CHANGE ALL THE TIME, RAPIDLY. THIS ADVICE MAY BE INVALID IN A FEW DAYS.

Note the risk management of Aerosol-Generating Procedures and preoperative assessment.… Read more

Aerosol Generating Procedures in the COVID era

THIS IS NOT A POLICY, PROTOCOL OR GUIDELINE. THIS IS A THOUGHT PRIMER. I AM NOT A PUBLIC HEALTH PHYSICIAN OR AN INFECTIOUS DISEASES PHYSICIAN. THESE ARE THINGS YOU SHOULD THINK ABOUT WITH YOUR TEAM WHEREVER YOU ARE IN THE WORLD.… Read more

THIS IS NOT A POLICY, PROTOCOL OR GUIDELINE. THIS IS A THOUGHT PRIMER. I AM NOT A PUBLIC HEALTH PHYSICIAN OR AN INFECTIOUS DISEASES PHYSICIAN. THESE ARE THINGS YOU SHOULD THINK ABOUT WITH YOUR TEAM WHEREVER YOU ARE IN THE WORLD.… Read more

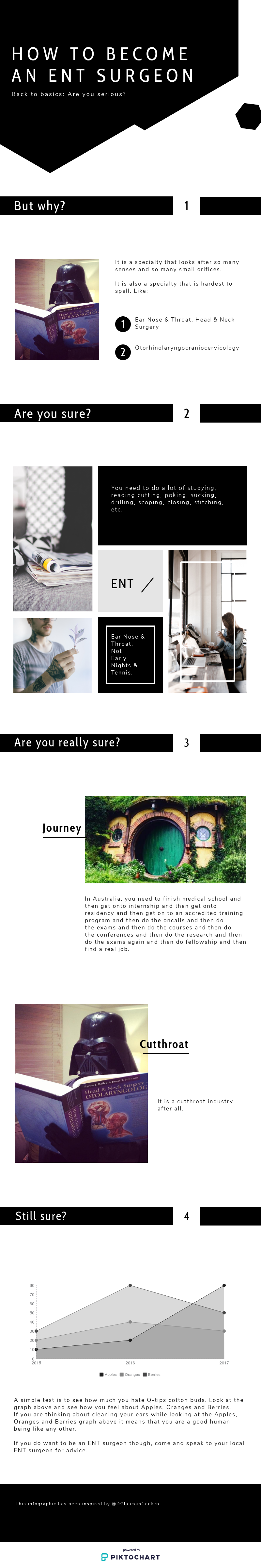

COVID19 and ENT Surgeons

ENT Surgeons and the COVID19 Pandemic

Updated 22nd March 2020

Key findings from literature as of today.

1. ENT surgeons are at higher risk and have higher rates of contracting the virus SARS-CoV2.

2. Thought to be due to high virus load in nose, nasopharynx and oropharynx, even in asymptomatic carriers hence we may be examining and operating on asymptomatic patients with high viral load.… Read more

Life in a Pandemic

Brace. Brace. Brace.

Brace. Brace. Brace.

The next couple of weeks and months will be tough for all of us. There is no need for panic or hysteria but there is need to prepare. The flu pandemic in 1918 tore through the globe and killed somewhere between 20-50 million people.… Read more

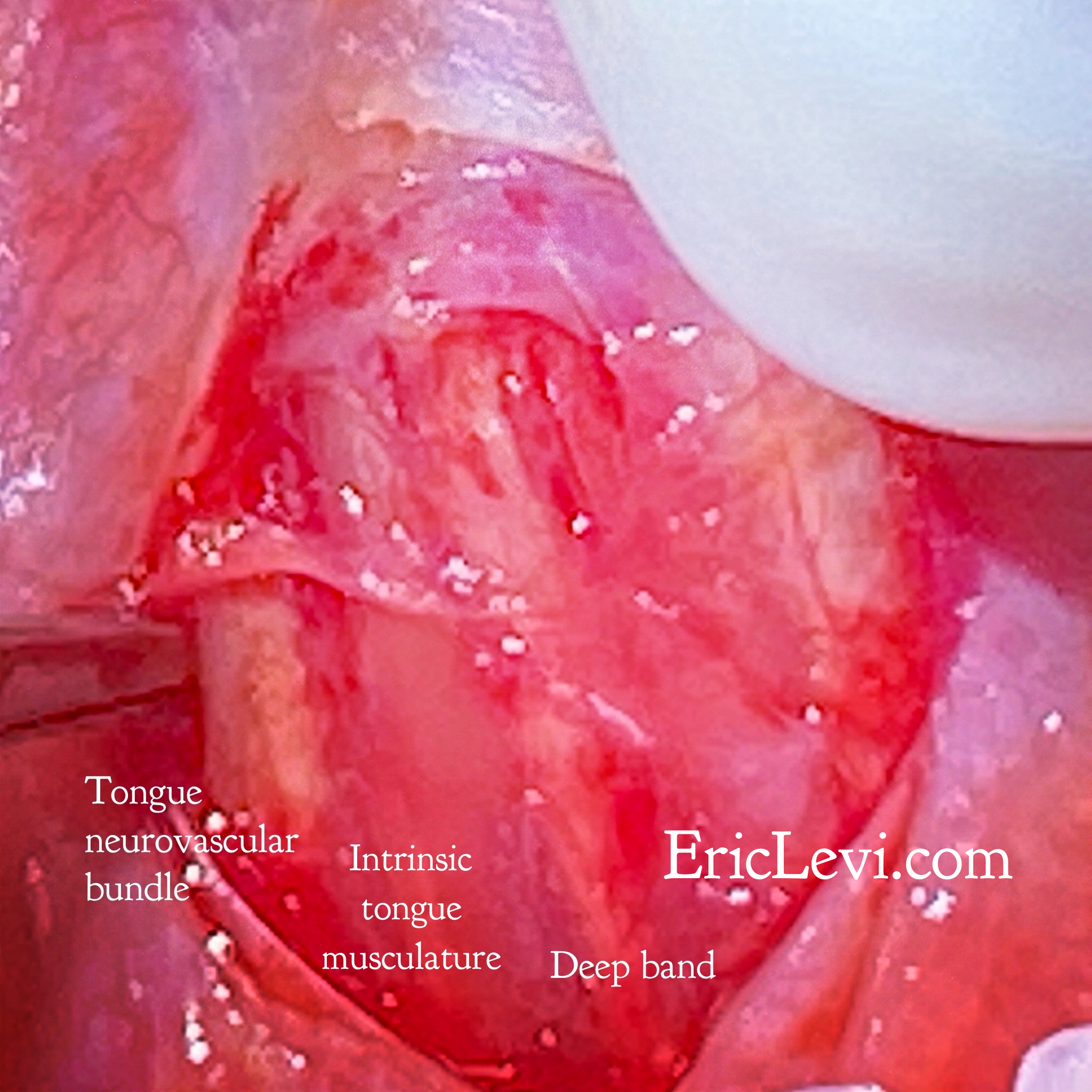

Tongue ties, Lip ties. Frequently asked questions.

I sincerely empathise with the many mothers who are struggling with breastfeeding and who are confused about the role of tongue ties in breastfeeding, swallowing, sleep and speech. I hope I can write something of value to help you navigate this issue.… Read more

I sincerely empathise with the many mothers who are struggling with breastfeeding and who are confused about the role of tongue ties in breastfeeding, swallowing, sleep and speech. I hope I can write something of value to help you navigate this issue.… Read more

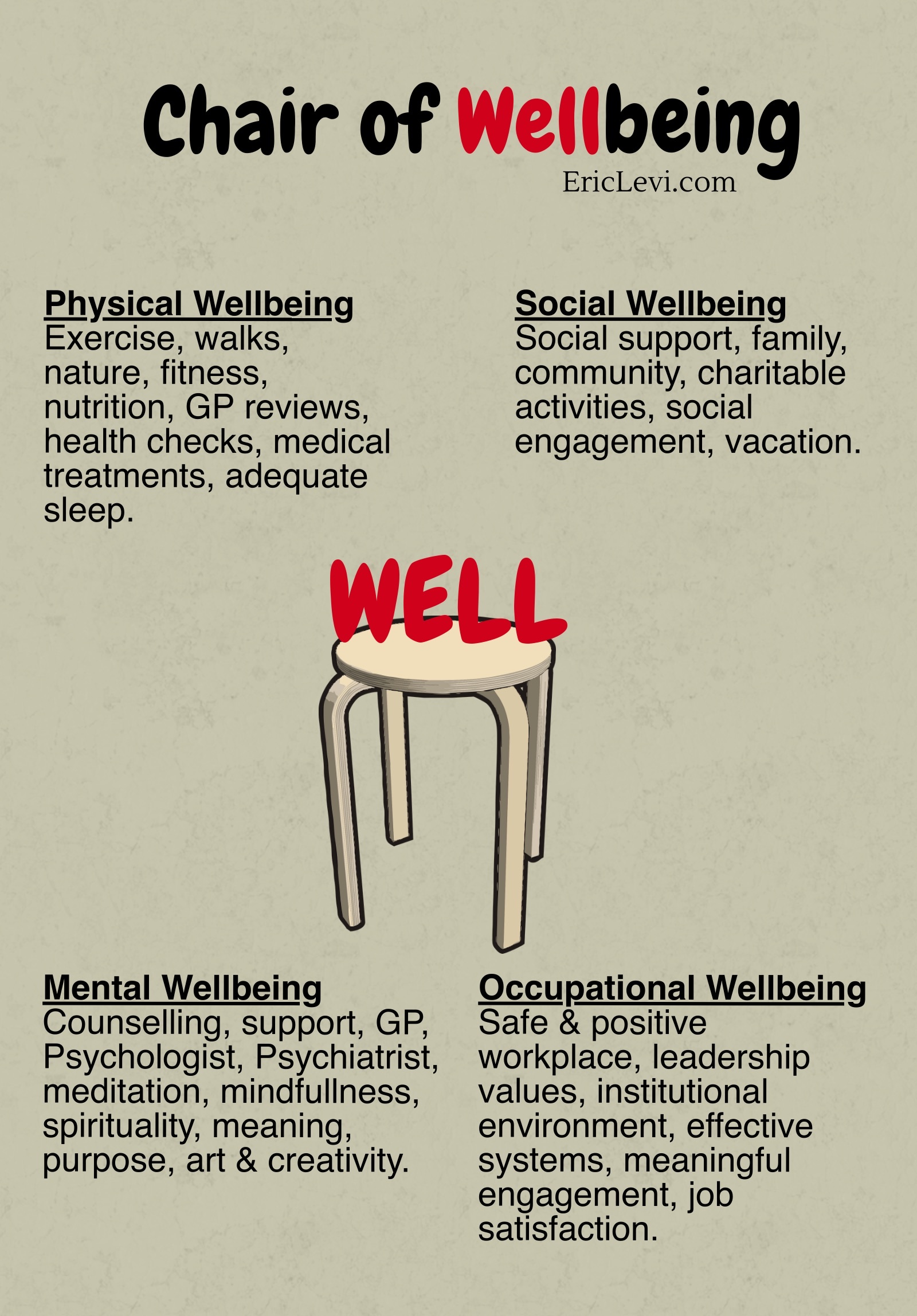

Wellbeing Chair

You’re welcome to use this concept freely as a primer for discussion around the issue of wellbeing in your community.… Read more

Social Media in Surgery

Some thoughts for Social Media Panel at the American Academy of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery Meeting 2019, New Orleans.

Social Media is here to stay. The lines between traditional media, digital media and social media are blurred. Contents of traditional media are presented on social media platforms.… Read more

Saliva Surgery & Sialendoscopy

Saliva is good for your health. Saliva provides immune protection, chemical digestion and protects the teeth from dental caries. Too little saliva is debilitating. The mouth is too dry, tongue sticks on the roof of the mouth, taste is altered, speech and swallowing is difficult.… Read more

…

…