Introduction presented at The Royal Children’s Hospital Grand Round Feb 2019.

Grand Rounds are about the big things that matter most to our patients. Grand Rounds are about milestones of the past, victories of the present and forecasting of the future. At their core, Grand Rounds are about the things that would make our patients’ lives better in Melbourne and beyond.

I commend the RCH for choosing the matter of Clinician Wellbeing as the Opening Grand Round topic this year, because the wellbeing of clinicians directly influences the work of clinicians and therefore the wellbeing of our patients.

I know what you’re thinking. What a fluffy touchy feely subject. What a new age subject. What a politically correct subject. We should really be talking about things that are of greater cosmic importance, such as the beauty of the human larynx, the acoustic intricacies of the middle ear or the exquisite grace of a neck dissection. We could talk about them all day. But today I would argue that of all the topics that will be discussed over this coming year, this is the one that will hit closest to home. This is the one that would potentially alter the course of our community as a whole. Because unless we appreciate the human cost of a clinician burnout, the financial loss of disengaged clinicians or the devastating loss of a human life to suicide, we will not make peace with our present to change the future.

A word of warning. We are entering into a space full of raw emotions. I understand that for some of us, this topic is very personal. You’ve been burned out, exhausted and depressed. You may even have contemplated suicide. You’ve sacrificed everything to be where you are, and yet it is not enough. You have faced bullying, harassment and discrimination. You sit in a room full of high achievers all suffering from the same impostor syndrome wishing we were half as good as the person sitting next to us. I too know the Dark Side of being a Doctor. I have been deeply burned out. I have lost a friend and colleague to suicide. The wounds of training are still raw. Hear us out. There are formal avenues of help available. Please access them. And there are informal ones too. Your colleagues and many like us are here to help you.

But this is the community where we need to audit our own morbidity & mortality. To use a surgical language, we need to debride this wound, bring it together gently and allow it space to heal. We need a good scrub and a good think about where we should go as a community. We hope that this Grand Round is the first catalyst to an open conversation and future action. Note that I use the term clinicians to include all clinicians because this problem is not confined to doctors. Allied health and others face similar problems too. Medical culture affect nursing culture and vice versa. But today we will be focusing on challenges and solutions unique to doctors.

Catherine Crock, Jane Munro and many others including Heads of Units and the Executives have done a lot of work in this arena. My job today is simple. I am the surgeon so I get to be the problem. I was an easy pick to set the problem because you know, the surgical ABC is Arrive, Blame, Criticise. I am surgically trained to find the problems.

3 words today for you to think about:

Context

Culture

Challenge

Context.

Do we really have a problem in health care or is this the song of an acopic generation? Let me remind us that Medicine is not what it used to be. There is no longer the ease and simplicity of the Doctor-Patient relationship. It is now the Doctor-EPIC-patient relationship. Between me and the patient stands technology, KPI, research, publications, funding, grants, ethics, admin, resource allocation, bookings officer, legal restrictions, social media, data collectors, patient advocate, lawyers, etc. The explosion of knowledge means that the typical resident today has to deal with way more digital pings, complex conditions and treatment regimes compared to doctors in the past. We are asking today’s doctors to be doctors, data collectors, social advocates, information officers, legal experts, and technological wizards. We’ve lost our sense of control over our work. We’ve lost our sense of support. And we’ve lost the meaning of our work.

Given the ever-increasing knowledge base and expectations on doctors, no wonder we have been hiding this elephant in the room.

Here are some stats we don’t really want to hear. Based on Beyond Blue’s survey. 1 in 5 of us has had a diagnosis of or treatment for depression. 1 in 4 has had thoughts of suicide and 1 in 50 has attempted suicide. Do not dissociate yourself from these stats. In an auditorium like this, depression and suicidal thoughts abound. Mental health is one elephant in the room. This needs to be acknowledged and professional support from psychologists and psychiatrists need to be sought. Engage your GP and seek formal assistance.

There is another elephant. A separate and possibly bigger issue of burnout. Burnout is not depression. They may be correlative or associative, but they’re not the same thing. Depression is a mental health diagnosis based on DSM5, ICD10 criteria. Burnout is not a psychiatric diagnosis. It is a psychological state due to chronic occupational stress characterised by emotional exhaustion, low professional efficacy and high cynicism. We’re mentally exhausted, we are not efficient at work and we gossip cynical about other units. Based on some studies, at any one time about half us meet the criteria for burnout. Which means that half of our doctors in this hospital may not be functioning safely or at full capacity. That’s bad for patients and bad for business.

Who gets burned out? Front line doctors and certain high acuity specialties. Paediatrics sit somewhere in the middle. What causes burnout? You would think that compassion fatigue would be a major contributor, but no that’s actually second lowest. The top four reasons for burnout has nothing to do with patients. They’re bureaucratic and clerical challenges.

How do we beat burnout? Much of the simplistic reductionist solution thus far has been directed at the individual level. It is imperative that we doctors look after ourselves. For the first time last year, The Physician’s Pledge drafted by the World Medical Association specifically says that I will attend to my own health and well being in order to provide care of the highest standard. If we can’t look after ourselves, we can’t look after our patients.

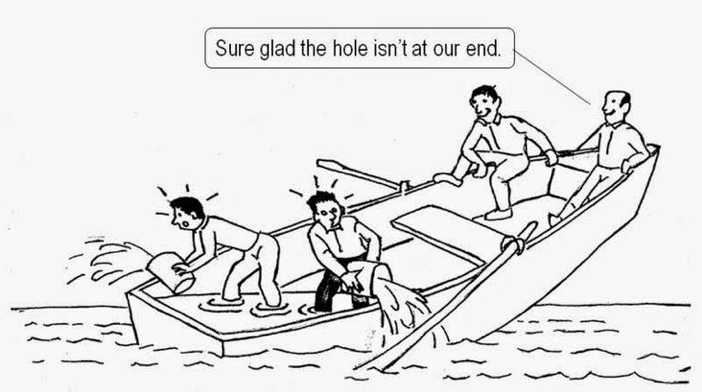

But that is not enough. The huge problem of doctor burnout and mental illness can’t be fixed with more yoga or meditation classes. They are important but they can’t be the only solution. When the boat is sinking, we need to find solutions together, not argue over jurisdictions and rules. This isn’t a junior doctor specific problem, because seniors burn out. This isn’t a Royal College specific problem, because doctors interface more with the working environment than they do with the College. This isn’t a specialty specific problem because it affects all specialties and how we engage with each other. This is our problem. It’s our institution, our HR, our college, our specialty, our leadership, OUR problem.

Which takes me to the second point.

Culture.

You can have the best workplace regulations and protocols, but if it is embedded in a culture of overtime, unpaid labour, hierarchical abuse, it will fail the doctors. Institutional culture eats regulations and protocols for breakfast. Hierarchies are not inherently bad. It is the misuse and abuse of that hierarchy that is bad. I extend a warm welcome to the new registrars, residents and consultants starting this week. Within the next couple of weeks, you will discover the RCH culture and perhaps you can tell us whether our values align with our culture. Is this a place where every person is truly valued and supported to reach their fullest potentials for their patients? Is this a place where people tiptoe around senior doctors or is this a place where the senior doctors make room for the younger ones to thrive and grow?

Having worked in Canada, Brisbane and Auckland, the impact of organisational culture on staff wellbeing is significant. There is a general global medical culture, but there are also specific local cultures. Each department within RCH has a slightly different culture. This departmental culture is set by the Leader, the Language and the behaviour within that department.

Therefore our solutions to burnout must not only address individual factors but also institutional factors. This is where Executives, HR, Heads of Units and Supervisors come in. We need formal systems, programs and structures to act like a safety stretcher to support our colleagues. The difference between your garden and my backyard weed-infested forest is that your garden is planned and tended carefully. We need to plan and tend to our institutional environment so our colleagues can thrive. Multiple papers have been published with evidence-based recommendations of various kinds. Addressing the institutional factors is critical in changing culture. Jane and Cathy will have some concrete suggestions. These programs and activities are simply scaffolds. They’re there to support culture. If we have a strong positive workplace culture we won’t need to rely too heavily on these scaffolds.

Challenge.

Finally, having seen the context and appreciate the culture, we have to face our challenge. What is our challenge? To be a great children’s hospital, leading the way. A lot of work has been done by Dr Munro, Dr Crock and many others behind the scenes. There is a groundswell of support. There is a positive momentum being felt amongst our colleges and institutions. None of us are experts in this arena, but if we are going to be a leading children’s hospital, we need to take the risk and embrace this challenge. Our investment on doctors’ wellbeing today will bear fruit a long way into the future. We can be a beacon of light on this matter. We can show others how it can be done. The Clinician Compact is one way of defining those things that matter to us. This is our DNA and this is how we can change the narrative around doctors wellbeing. So far the narrative has been about hierarchical abuse, depression and suicide. I strongly believe that the RCH as a major player can create a momentum to reach the tipping point to change the narrative into a positive one here in Melbourne and beyond.

Ultimately, our patients deserve exceptional care delivered by fully engaged compassionate doctors who are free from burn out. The core of our strategy is to unlearn and relearn what it means to be human and how to be humane together in health care. I shall hand over to Dr Jane Munro for some practical advice on how we can thrive together in this space…