This presentation was given at my Division of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery Grand Round. These are my key introduction and summary points for your enjoyment with a whole section of papers and data excluded. These are my opinions and not those of any persons or organisations I may be associated with. This blogpost is not a scientific or commercial presentation.

This presentation was given at my Division of Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery Grand Round. These are my key introduction and summary points for your enjoyment with a whole section of papers and data excluded. These are my opinions and not those of any persons or organisations I may be associated with. This blogpost is not a scientific or commercial presentation.

Please, relax. Many would understandably approach this topic with a set of preconceived ideas about the surgical robot. Disclosures: I am not a robot or a robotic surgeon. I do not own a robot or any shares in any robotic company. I am not a proponent or an opponent of robotic use in surgery. I am not selling any robot or any robotic ideas. I am a Head & Neck Surgeon trained in the conventional open surgical approach and the Transoral Laser Microsurgery techniques. I have attended a TORS seminar and seen the robotic operations performed several times in Australia.

Why explore robotics? Because of these three reasons:

- As a doctor, I have a duty of care to my patients to objectively explore new treatments.

- As a surgeon, I do not need to be an early adopter of every new technique or technology, but I should be an early explorer.

- And as a professional, we police ourselves. We need to know if the robot is an effective tool for the general public.

The problem is that when we have a fancy expensive hammer, everything starts looking like a nail. The robot is not meant to replace all open operations. It is not meant to cure every disease. The robot has its unique place. We need to use the right tools for the right patient for the right indication at the right time with the right team.

It is said that all truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident (Arthur Schopenhauer). We have seen these waves of resistance historically in medicine: handwashing, H.pylori, EBV & HPV oncogenic virus. And specifically the challenges faced by previous generations of ENT surgeons in laser surgery, bionic ear, endoscopic sinus surgery, endoscopic ear surgery, etc.

Brief history of Robotics: 1921 – Czech playwright, Karel Capek, first coined the term robot, based on the Czech word “robota” for slave or serf, in his play, Rossum’s Universal Robots. His brother Joseph Capek wrote the short story “Opilec,” in which “automats” were described. 1940s – Isaac Asimov wrote multiple short stories on Robots in society. Major key difference is that surgical robots are passive tools that require surgeons to drive them. Surgical robots do not operate on their own. They are extensions of the surgeon’s eyes and hands.

History of Surgical Robotics. 1985: PUMA560 Stereotactic brain biopsy. 1988: PROBOT London prostate surgery. 1992: ROBODOC (Curexo Technology, Fremont, CA), a computer-guided mill used to core the femoral head, ACROBOT (The Acrobot Company, London) for knee replacement and temporal bone surgery (drill pressures). 1997 a reconnection of the fallopian tubes operation in Cleveland using ZEUS. May 1998, Da Vinci surgical robot performed the first robotically assisted heart bypass at the Leipzig Heart Centre in Germany. October 1999 the world’s first surgical robotics beating heart coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) was performed in Canada by Dr. Douglas Boyd and Dr. Reiza Rayman using the ZEUS surgical robot. November 22, 1999 – the first closed-chest beating heart cardiac hybrid revascularization procedure is performed at the London Health Sciences Centre (London, Ontario). September 7, 2001, Trans-Atlantic Telerobotics – Dr. Jacques Marescaux and Dr. Michel Gagner, while in New York, used the Zeus robotic system to remotely perform a cholecystectomy on a 68 year old female patient who was in Strasbourg, France.

Where’s the robot today in surgery? 85% of radical prostatectomy in the U.S. is performed with the robot. Biggest users are those with difficult access regions: Urology, Gynaecology, Cardiothoracic, while ENT is relatively new and late to the game. Here in ENT, the Robot rides 3 ENT epidemics: HPV positive oropharyngeal SCC, thyroid cancer and OSA.

Big Questions: Is it safe? Is it surgically efficient? Is it oncologically effective? Is it useful? Is it user-friendly? Is it cost-effective? Is it better? In comparing techniques, are we comparing apples with oranges? Open vs TORS, RTx vs TORS, TLM vs TORS, RTx vs Open vs TLM vs TORS, CRTx vs Open vs TLM vs TORS. Without data, you’ve only got an opinion. Entering “Transoral Laser Microsurgery” in Medline Search term from 1964 brings up 193 papers, while “Transoral Robotic Surgery” has 337 papers associated with that term. There is a lot of data already out there with regards to the use of TORS.

From Li & Richmon “Transoral Endoscopic Surgery New Surgical Techniques for Oropharyngeal Carcinoma”. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 45 (2012) 823–844.

Learning curve for TORS (TransOral Robotic Surgery):

- Mean operative time decreased by almost half

- Total setup time decreased

- Intuitive skills acquisition

- No previous TLM (Transoral Laser Microsurgery) or endoscopic skills required

Current ENT Robot use in U.S.

- 2009: FDA-approved for T1 T2 OP tumour

- 2014: FDA-approved for benign BOT procedure

Current credentialing process in different institutions:

- Preclinical: courses, simulators, labs

- Proctored cases: 2-10

- Maintenance of certification: 10 in 1yr or 25 in 2yrs with 10 conventional open cases per year

Skills progression in robotic techniques.

- (1) benign tonsillar pathology;

- (2) lingual tonsillectomy;

- (3) lateral oropharyngectomy (“radical tonsillectomy”);

- (4) resection of the hemi-tongue base; and

- (5) supraglottic laryngectomy.

In summary:

Is it safe?

- Yes. TORS is proven to be safe.

Is it surgically efficient?

- Yes. TORS procedures are shorter than conventional open surgery. Docking time 10-20min on average. Significantly shorter overall length of hospital stay compared to conventional surgery.

Is it oncologically sound?

- Yes. For Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: better primary unknowns identified, better clear margins, DFS rates comparable to TLM/open, reduced G-tube & trache rates, long term functional outcomes better than conventional surgery.

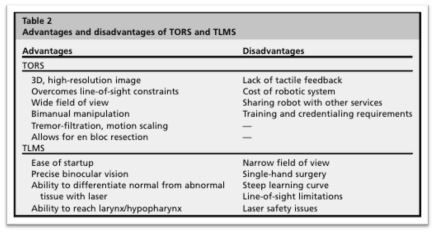

TORS vs TLM?

- Equal oncological and functional outcomes. Both better than conventional surgery. Studies underway to compare TORS/TLM vs Rtx/CRTx. TORS superior for access & visualisation (in difficult cases).

TORS for thyroid?

- Not in Australia/New Zealand or North America. Duration of procedure longer. Length of stay unchanged, benefit shown only for scar. Complication rates notable. Public purse significantly affected. May be appropriate in some cultural context out of pocket.

TORS for OSA?

- Not yet/maybe. Evidence for surgery in OSA is confusing and controversial. Hard to prove robotics will clear this controversy. Need more evidence here

TORS for paediatric airway?

- Maybe. Hard to develop evidence base in this population. Better, smaller future robots may be effective.

Is it cost-efficient?

- Big purchase and maintenance fee. Case costs and hospital care costs cheaper compared to conventional surgery and compared to radiotherapy. Definitely cost efficient in Urology & Gynaecology. Questionable in low volume ENT. Robotic centres which include Urology, Gynaecology and the less frequent Cardiothoracic and ENT is the most cost-efficient way for public purse.

Other things I’ve learned

- Be critical not cynical

- Surgical access is where the robot excels

- The robot in 10 years will be a better tool than now. Surgeons need to drive this improvement (haptic feedback, laser, finer graspers, etc).

- Like any surgical technique there’s a specific place for the robot in the toolbox of the ENT community

Is the robot better for the surgeon?

- Robotic skills is intuitive

- Driving a Ferrari is easier/better/more fun than driving a Toyota, but at what cost?

- The robot is an extension of your surgical aptitude, like the endoscope, the IGS, etc.

- The robot makes access and visualisation in difficult anatomy better, but the robot doesn’t necessarily make you a better surgeon.

- A fool with a tool is still a fool. A slow surgeon with a robot is still a slow surgeon.

Is the robot better for the public purse?

- Not from an ENT point of view only.

- But likely better collectively (Urology, Gynaecology & ENT).

Is the robot better for the patient?

- Yes, for OPSCC and a few pharyngeal and laryngeal pathologies but TORS not yet freely accessible.

- There’s currently a cheaper, more accessible, equally effective tool in trained hands: TLM.

- Only few will be truly disadvantaged by lack of robotic access (those with difficult surgical access to the oropharynx from anatomy, pathology or prior radiation).

Where to now?

- Robotic surgeons, keep doing your stuff. Keep reporting.

- Try out the robot when you can (simulators in conferences, courses)

- Drive the technical improvements.

- Drive the price down.

- Drive the accessibility for patients.

- TLM & TORS should be considered as similar approaches.

- In the meantime, TLM is just as good, or conventional open surgery, if TLM is not available or not indicated.

- The vast majority of ENT patients will not be disadvantaged by a lack of robotics.

- For a few patients, lack of TORS/TLM would mean conventional surgery with associated morbidities and longer hospital stay but similar prognosis overall.

Keep innovating for the sake of our patients.